Doctors

Department of Musculoskeletal Oncology

The department of Musculoskeletal Oncology has expertise in managing bone and soft-tissue cancer/sarcoma cases. Nearly 200 patients diagnosed with primary bone and soft tissue sarcoma and metastatic disease are managed annually at our hospital. As musculoskeletal oncologists, our team provides expertise in precise diagnosis, appropriate decision-making in management and expert surgical care. The experience and expertise in reconstruction surgical techniques and limb-salvage procedures have helped to save hundreds of limbs every year and restore normal function to patients.

We have collaboration with regional centers for Radiation therapy

Patient Information guide / Frequently asked questions

Sarcomas are tumours derived from mesenchymal cells (bone, cartilage, blood vessels, muscle, fat, nerves, and connective tissue, including that present in the organs). They can develop at any site in the body. Sarcomas are rare cancers accounting for less than 1% of all cancers. There are many different types of sarcomas, but they are usually grouped into soft tissue sarcomas or bone sarcomas. We specifically deal with sarcomas in the bone and soft tissue.

Bone sarcomas are primary bone cancers and rare, accounting for about 0.2% of all malignant tumours. They are common in children, teenagers, and young adults, although much less commonly, they can occur in the older age group of patients. The exact aetiology is still unknown. The commonest types of bone sarcomas are osteosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma, and chondrosarcoma. They can arise at any site in the body, although they are most commonly in limbs and the pelvis. Initial symptoms usually include:

Non-mechanical pain (pain when not doing any activity).

Swelling of the affected bone.

A fracture due to very minimal trauma.

Malignant bone sarcomas are aggressive tumours usually treated with a combination of surgery and long courses of adjuvant therapy, mainly chemotherapy. Modern surgery aims at limb salvage surgery (preserving the limb function following removal of primary tumour, while at the same time preserving the limb function (or another body part) wherever possible. Limb-salvage surgery is usually done by replacing the bone with endoprosthesis or employing biological methods of reconstruction. Radiotherapy is sometimes used after surgery or instead of surgery if a surgical option is not viable.Aggressive benign tumours like giant cell tumours are managed well with intralesional curettage surgery.

Soft tissue sarcomas account for less than 1% of all malignant tumours. The cause of these tumours is not known, although they may be associated with previous radiotherapy, some toxins, and very rarely, may be hereditary. They can affect any age group, although they are more common in the middle-aged and elderly and less common in younger age groups. There are many different histological subtypes of soft tissue sarcomas, although the commonest include undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, liposarcoma, myxofibrosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour. Nearly 60% of soft tissue sarcomas arise in the arms or legs. The commonest sarcoma arising from the gut is gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST). The signs and symptoms of sarcomas are often the first sign of a lump in an arm or leg. Worrying features that might indicate a sarcoma include a size greater than 5cm, a lump increasing in size, and increasing pain. Radiotherapy is usually indicated as adjuvant therapy in managing soft-tissue sarcomas.

The most important part of diagnosis in sarcoma is to take a sample of the tumour, called a Biopsy. Biopsy is best done by trained specialists as incorrect procedures can compromise limb salvage. A pathologist examines the biopsy under a microscope to confirm whether there is cancer and to grade the type of sarcoma if present based on aggressiveness. Most biopsies are done under anaesthesia using ultrasound or fluoroscopy in theatre. CT-guided biopsies too are done for suspected tumours in anatomically challenging areas. Immunohistochemistry and Molecular genetics to identify characteristic chromosomal translocations and gene mutations (abnormalities of the genetic material) now are advances in sarcoma diagnosis.

Imaging/Scanning is essential to determine whether the tumour has spread anywhere else in the body or is confined only to the primary site. This is called Staging. Soft-tissue sarcomas of limbs most likely spread into the lungs, whereas those of the abdomen or colon commonly spread into the liver. Bone sarcomas most commonly spread to the lungs and bones. Staging scans may include MRI scans, CT scans, bone scans and PET scans.

Based on the staging of the disease, the treatment plan is decided by the multidisciplinary team. Surgical treatment is an essential arm of sarcoma management. The various options include:

Wide resection of tumour with endoprosthesis(implant) reconstruction

Wide excision surgery

Local intralesional surgery

Amputation

CT-guided ablation procedures for certain tumours

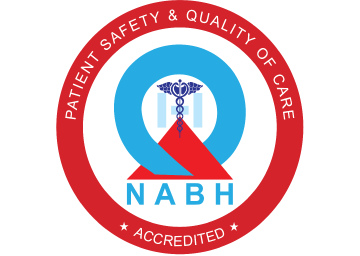

Figure 1: Bone bank is used to store bone to fill gaps and removal of tumour. These bones are collected from surgery and amputation specimens. They are thoroughly cleaned and processed through a sterile process before using them again. These donated bone from patients stored in a bone bank (a,b) can be used to fill defects after meticulous removal of disease in tumours like giant cell tumour (GCT) (c,d). Benign tumours are treated with local removal of tumour and complete curettage using high speed burr to clear all microscopic tumour cells.

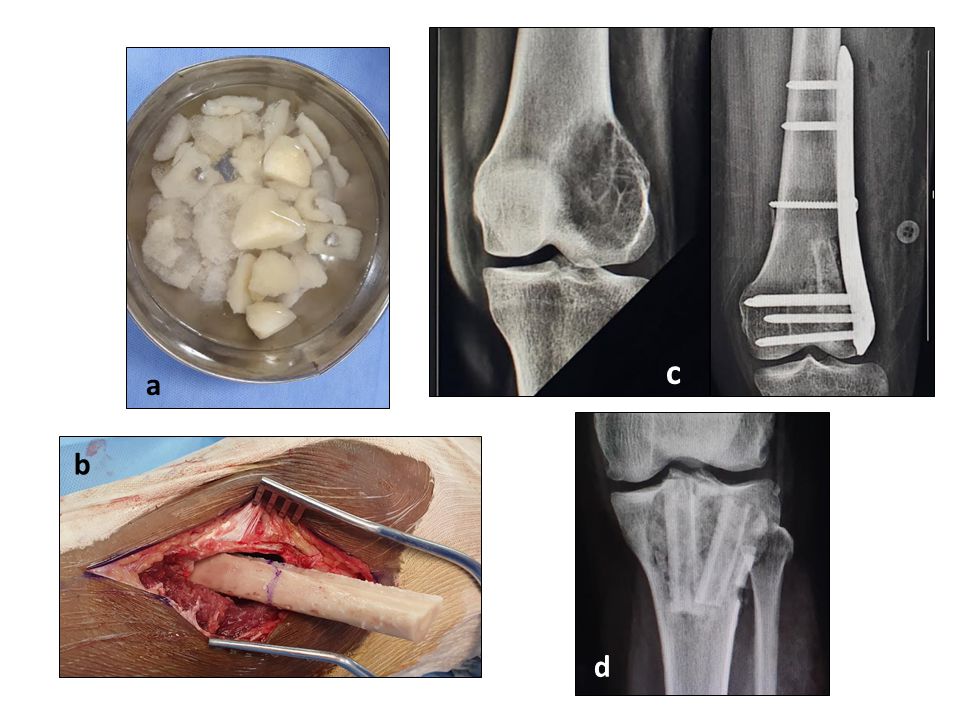

Figure 2: Osteosarcoma is a malignant bone-forming tumour. This commonly occurs in the bones around the knee joint. Treatment involves pre-operative chemotherapy to shrink the tumour. Surgery then involves removal of the cancer with normal bone and limb-preservation is done using endoprosthesis (c). The specimen is assessed to see for the necrosis and effect of chemotherapy on cancer cells.

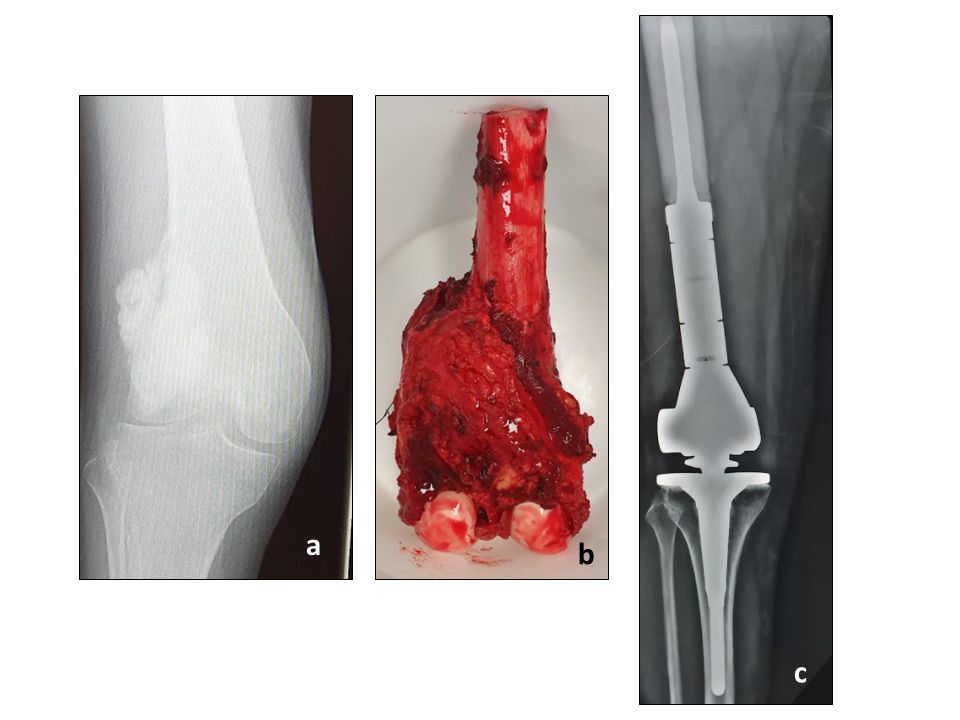

Figure 3: Specimens of excised bone in Chondrosarcoma (malignant cartilage tumour) which is helpful for pathologists to assess whether the complete tumour has been removed. Cut sections of the tumour are seen to see if there is any normal tissue covering the tumour tissue (margins). This helps us assess whether the entire tumour is removed. Complete removal of tumour with no tumour tissue in the edges (negative margins) is associated with better outcomes.